Fat Pad Atrophy

The One Place You Don’t Want to Be Thinner – Fat Pad Atrophy

Given the potential of plantar fat pad atrophy to cause significant pain and adverse effects on function, particularly in patients with diabetes, these authors discuss keys to making an accurate diagnosis and outline current treatment options.

History

Our feet endure a lifetime of use and, at times, abuse. In 75 years, the human foot traverses over 100,000 miles.1 One consequence of this excess “mileage” is atrophy of the plantar fat pad, a common complaint that can cause significant pain and disability. Yi and colleagues documented that fat pad atrophy is the second most common cause of heel pain following plantar fasciitis.2 Associated with various conditions such as diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, trauma, chronic steroid use and old age, fat pad atrophy results from atrophy of adipose tissue along with degeneration of the collagenous septae (sheets) that impart resiliency.

Treatment

Despite fat pad atrophy being a common complaint within the podiatric population, treatment is often difficult and may result in pain and limitation. Treatment for the most part has concentrated on offloading the involved area via padding, inserts, corrective osteotomies and resections.

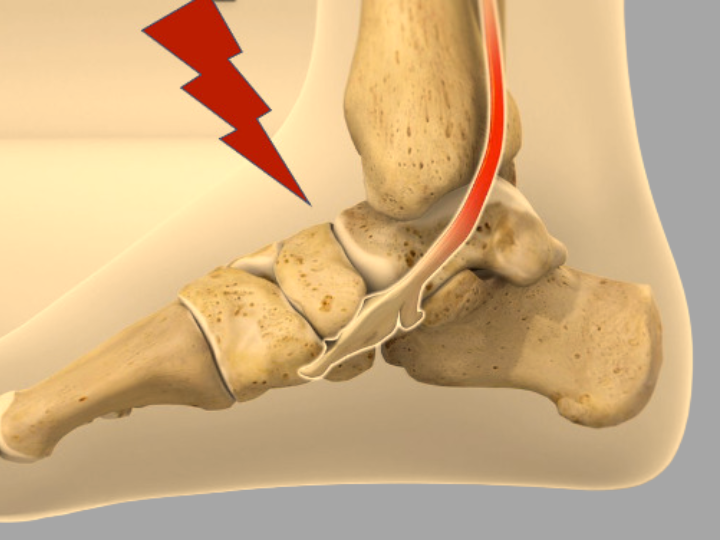

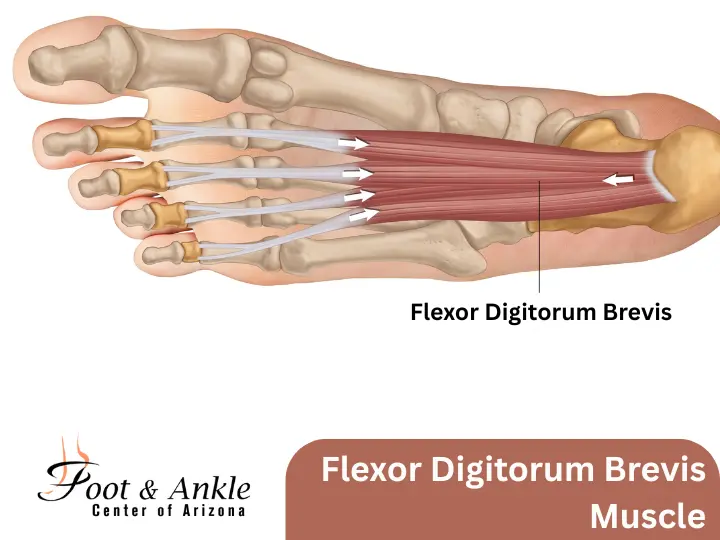

Function

The main function of the plantar fat pad is to protect the underlying structures (neurovascular tissues, sensitive periosteum, ligaments and tendons) from undue pressure and shocks. Various authors have studied and described the specialized anatomy of the plantar fat pad, a “honeycomb” structure with fat globules completely enclosed by fibroelastic septae.3-7 These septae connect to the skin, superficial fascia and underlying periosteum, and help prevent deformation, compression and displacement of the fat globules in the compartments. They do not normally allow fluid or fat leaks, keeping the shock absorbing fat globules in place over the sensitive structures beneath.

Pertinent Insights On The Pathophysiology And Etiology Of Plantar Fat Pad Atrophy

How does the plantar fat pad fail? The general consensus is that atrophy of the fat cells combined with degeneration of the septae cause loss of overall volume and displacement, thus exposing the sensitive underlying structures to increased stress.2-5,8-10 This process is associated with multiple factors including increasing age, diabetes, neuropathy, rheumatoid arthritis, vascular disease, collagen disorders, corticosteroid use, trauma and orthopedic deformities such as hammertoes.2,4-8,10-14 Clinicians have reported cases of plantar fat pad atrophy secondary to steroid injections for a neuroma.15

Increasing Age

One of the most significant associations of fat pad atrophy is increasing age. Commenting on fat pad atrophy in the aging foot, Hsu and colleagues stated that “the most obvious abnormality in the senescent heel is the presence of more numerous, thicker and considerably fragmented elastic fibers.”8 They also noted “a gradual loss of collagen, a decrease in the elastic fibrous tissue and a decrease in water content occur in aging pads.”8 Their study compared the heel pads of younger (age 18-36) to older (age 62-78) patients with ultrasound in regard to unloaded heel pad thickness (UHPT), compressibility, stiffness and shock absorbency. While unloaded heel pad thickness was significantly increased in the elderly — a result they attributed to greater BMI in the older population — the senescent fat pad was less compressible with decreased shock absorbency. The stiffness was also increased in elderly fat pads, albeit insignificantly.8

Diabetes

The association of diabetes with fat pad atrophy is controversial. The literature is equivocal with some articles claiming no link and others demonstrating a clear association.10,14,16-18 Regardless of whether diabetes itself is a contributing factor to fat pad atrophy, the condition can lead to serious consequences (such as ulceration and resulting infection)in a patient with diabetes. Indeed, Gooding and coworkers found via sonography that patients with diabetic ulceration (or a history of ulceration) had significantly thinner heel pads than patients with diabetes without ulceration.19 Avoiding or treating fat pad atrophy in patients with diabetes may decrease the risk of ulceration and other untoward consequences.

Essential Diagnostic Tips

The diagnosis of fat pad atrophy is usually a clinical one with thinning of the fat pad and resulting underlying prominences easily palpated. Yi and coworkers discussed the clinical diagnosis of plantar heel fat pad atrophy and how to differentiate it from other causes of heel pain, such as plantar fasciitis. They found that people with plantar heel fat pad atrophy presented with bilateral (both sides) centralized heel pain (as opposed to unilateral medial tubercle pain) that occurred after prolonged standing or walking, and at rest. Plantar fasciitis, on the other hand, was more associated with unilateral medial calcaneal (heel) tubercle pain and post-static dyskinesia (difficulty moving).2

Medical Imaging

Even though fat pad atrophy is mostly a clinical diagnosis, imaging can at times be useful. Yi and colleagues discussed the clinical aspects of fat pad atrophy diagnosis and were able to diagnose it by ultrasound if the fat pad was less than 3 millimeters, a factor which helped in differentiating fat pad atrophy from other causes of heel pain.2 Turgut and coworkers utilized plain radiography and the “visual compressibility index” to diagnose fat pad atrophy. They compared loaded heel pad thickness to unloaded heel pad thickness and found that in the normal patient, the former is approximately half of the latter.7 For the diagnosis of fat pad atrophy, clinicians have used other imaging modalities as well, including computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging and even ambulatory pressure pads.3

Current And Emerging Treatment Concepts

Currently, the treatment for fat pad atrophy consists mainly of offloading and cushioning via padding, shoe inserts and modifications. These are particularly important in neuropathic patients. However, frequently patients only get minimal relief or experience recurrent ulceration. One may attempt additional offloading surgically via osteotomies or resections. Alternative options are available should fat pad atrophy persist and for candidates unsuited for osteotomies or resections although the evidence supporting these treatment modalities is limited.

The future will probably bring new and improved treatments for fat pad atrophy as well. For instance, some dermal fillers used to reduce facial wrinkles and defects stimulate collagen production as part of their therapeutic effect.30 These fillers have the potential to rebuild fragmented collagen in the plantar fat pad, thus providing increased volume for shock absorption and decreased pain. Studies utilizing these agents are ongoing in the United States.

In Conclusion

Plantar fat pad atrophy is a significant cause of pain and limitation of function, particularly in the elderly. In the patient with diabetic neuropathy, it can have catastrophic consequences. While the diagnosis is usually straightforward, treatment can be difficult. Several therapeutic modalities have demonstrated varying degrees of efficacy. Other potential treatments are in clinical trials and will hopefully add to our therapeutic options.

https://www.podiatrytoday.com/expert-insights-therapies-plantar-fat-pad-atrophy